Made in America

We came away with a new understanding of American manufacturing.

We shipped our first batch of Made‑in‑USA pillow inserts on Tuesday, and we figured it was a good time to write about the moment.

We’ve wanted to manufacture inserts locally ever since we started selling these giant pillows. Back when we worked with a third‑party logistics (3PL) provider, storage costs were already a headache and we ended up taking a loss on this product. Things improved after we opened our own warehouse in LA, but a single import of 300 pillows still maxed us out. To give you a sense of the volume: they literally filled a 24‑foot truck—the one from our “Six‑Wheeled Porsche” post.

One thing we didn’t mention in that post is that this “Porsche” had a rail liftgate. They’re uncommon, and it’s the only time we’ve rented a truck with one. A rail liftgate offers a larger platform and easier leveling, which is friendlier when you’re loading from or unloading to ground level. It’s a different story when you’re using a loading dock, though.

There are a few pillow factories in the LA area that specialize in filling pillows and cushions—big‑box retailers like Target and Walmart often fill their private‑label bedding locally, too. Despite the high cost of rent (and, honestly, everything), you can still find all kinds of ghetto businesses in LA-the kind you'd think couldn't exist at U.S. wage levels. That’s partly because LA is one of the country’s major logistics hubs (lower logistics cost), and partly because of a relatively ample labor supply—we’ll come back to that later.

After making a couple of trial samples using the lining from our old pillows, we finalized the filling specs in May with one of the factories. Then the linings were delayed thanks to some more‑than‑epic drama (stay tuned) with the Chinese contractor who was supposed to handle them. The good news is we took the opportunity to bring lining production fully in‑house, handled by the same craftsperson who makes outfits for our plushes (possibly overkill, though).

Because of the same delay, we couldn’t ship the linings by sea—they would have missed our pre‑order fulfillment schedule. So we air‑freighted a small batch to LA and used the chance to observe the production process end to end. It wasn’t just a study of the U.S. industry; it also helped us decide on the ideal shipping‑box size. The factory scheduled production for August 26.

First, the factory that actually did the work wasn’t the first one we visited. The owner explained they had just purchased another facility—the one that ran Tuesday’s production—so it wasn’t as odd as it might sound; we had toured that site before production. They said they sent our job to the second facility because the first doesn’t have a press, which is essential for compressing our pillow inserts for shipping.

That said, the two factories were different. At the first, we saw Italian-made equipment in a tidy space but no workers on the floor. At the second, there were people working, but the filling machines were much lower-end. We’re quite familiar with that kind of staging—since we do business in China, where it’s common for a company to keep a beautiful space for customers while the actual production happens in the ghetto places. Not saying that’s what’s happening here—it just gave us déjà vu.

We don’t have photos of the second factory to show how “ghetto” it is—it’s honestly not bad, just not full of fancy equipment (which we didn’t need for this job anyway). We’re also not posting any shots with workers in frame, to protect not only their privacy but also their safety. The manager told us ICE has been active in the neighborhood, and they now keep the gate locked during work hours so agents can’t just walk in.

So, apparently, a significant portion—if not all—of the workers are not working legally (call them “illegal” or “undocumented” immigrants; we don’t judge either way). This is the labor advantage of LA we just talked about. And while you might think the factory pays these workers less than fair wages and thus takes jobs away from American citizens, what we saw is far more complex than that prejudice, and that’s the main point we want to talk about in this article.

On Tuesday morning, the factory put 6 workers on the job—and they were superb. The production was split into 8 distinct processes, and they handled each one crisply. They paid attention to every detail—they even caught a tiny stain (looked like sewing‑machine oil) that our Chinese team missed during inspection. The whole run took 90 minutes, including a 10‑minute test run and a 10‑minute break—so about 70 minutes of net work time.

While on site, we discussed what hourly wage it would take to attract American citizens to work there. We concluded that $20 would be enough—$25 at most (which is already much higher than any of us earns). Since most fast‑food places in LA can’t pay $20 an hour, and we all agreed the pillow factory is a better job than fast food (one of our team had direct experience in that industry).

Then it came down to simple math: say the factory pays $30 an hour. Add roughly 10% for federal and state payroll taxes, and the employer’s cost is about $33 an hour. Common benefits (unlikely here) like health insurance could add a couple hundred dollars per month per worker; let’s just call it $40 an hour all‑in. Why not $50 then? Sure—but note that $50 an hour is already higher than a lot of high‑tech positions around here (think about your own pay), so let’s stop there.

They worked 90 minutes, but we’re happy to count it as two hours. So: 6 people × 2 hours × $50/hour = $600 in notional labor cost in this more‑than‑generous scenario.

And how much were we charged for that 90‑minute job?

$2,500.

We brought our own linings and boxes. The only material they supplied was the filling. They used an Indonesian product—good (we wouldn’t have used it otherwise) but not as good as the Korean brand we use in our plushes. If we’d used our own filling, the cost for this job would have been around $400. There’s no reason theirs should be more expensive, especially since they likely get bulk discounts at their volume. Let’s even assume $500 because of a Trump tariff surcharge—they actually added that line item to our bill.

People will say, “Shipping from Indonesia costs money, too,” but folks outside logistics often underestimate how cheap ocean freight is. Put it this way: the factory that makes our filling is in Sichuan, and our own factory is in Guangdong. Ground shipping between those two is already more expensive than ocean‑freighting from Guangdong to LA. Same in the U.S.: The Korean brand we use has a factory in North Carolina, and it costs more to ship a ton of filling from there to LA than to ship it from Asia. In other words, ocean freight doesn’t move the retail price much.

If we reasonably assume that the material + labor are about $1,100 in this job, it means we paid $1,400 for something else.

We run a business—now a factory, too. We get that there are fixed costs, and we often have to explain that not all gross profit goes into our pockets (truth is, we fund the company out of pocket). But $1,400 in gross profit for a 90‑minute job? We wouldn’t dare think of it. There were three trial samples beforehand, but they told us those were subject to sample fees, which they waived as a goodwill gesture.

Math time again: Let's just say we spent 1/4 time of their working day (they work two shifts and the first shift run from 4AM to 12PM), which is about 1.25% of the month, assuming 20 working days a month. But they have two groups of workers on-site, one of them does sewing job so they're completely away from the filling business. So 0.625% is a more realistic assumption. Let's also say the factory takes a 20% net profit from our job, which is high enough and would equal to $500 in this case. Then $900 goes to the 0.625% monthly fixed cost, resulting a number of $144,000.

Does a small pillow factory of less than 20 workers need this much cost to operate? We rather leave this question to our readers. Do note that the workers are already in the marginal production cost so this $144,000 is only for:

- Rent

- Utilities

- Management salary

- Business taxes and Government Fees

We may never know the answer. What we do know is they didn’t single us out. While settling payment, we saw a couple of invoices for other customers, and the rates were about the same. We also shopped around before choosing this factory: another qualified shop in Burbank quoted $3,900 for the same job, per their pre‑“Trump tariff” quote.

Here’s another way to look at it: if a typical American small business—without in‑house capability or our connections—tries to produce a small batch of pillow inserts in China (or anywhere in Asia in the post‑“Trump tariff” era), they’ll likely pay more than doing it locally. That’s the logic the factory is pricing against.

Either way, the one possibility we don’t buy is that they pay their workers more than $100 an hour.

And that’s how the current trade policy of this country makes America great again: everything gets more expensive, regardless of where it’s made. Consumers pay more, and the money flows to capitalists and landlords. American workers don’t see real benefits from it—not to mention there weren’t even any American workers (depending on your definition) on this job—but that’s a different topic.

So why does an article criticizing capitalism have a truck as its title image? Readers of our backstage blog know how much we love talking about vehicles—really, trucks—because of our business routine. This time, we asked UPS to pick up some boxes directly from the factory, and we needed to bring the rest home. Instead of going to our old friends at Enterprise Truck Rental, we rented a brand new 2025 F-150 from National (same parent company anyway) for this lighter‑duty job. One teammate was flying out of town, so he could drop the truck at the airport too, saving even more money.

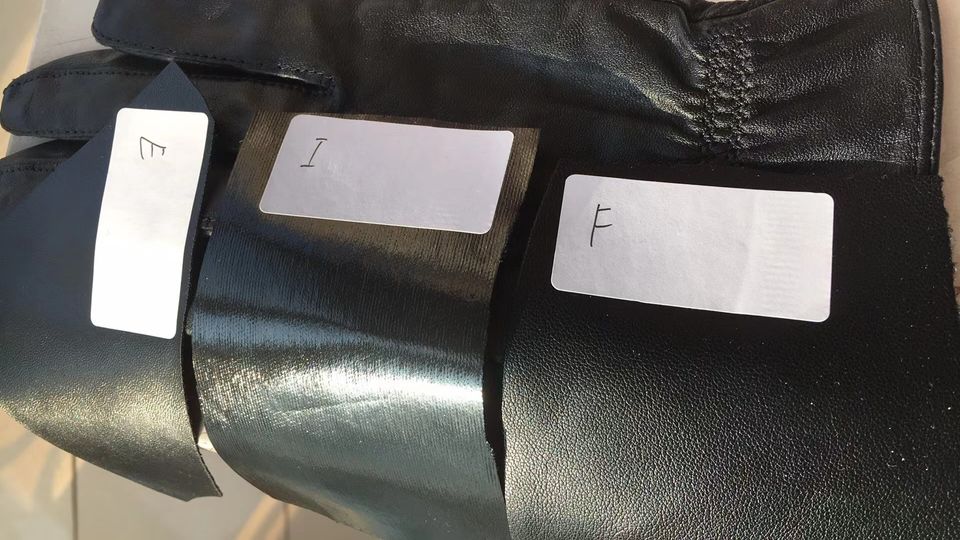

Loading pillows onto the F‑150. We picked up the cargo net from Harbor Freight. Made‑in‑China, of course.

The new F‑150 is amazing. For some reason, this one had the 3.5‑liter twin‑turbo V6 (400 hp). Not sure why a rental company would spring for the high‑power spec, but we’ve also rented a 3.5‑liter twin‑turbo Transit from Budget—a spec you don't see offered to consumers—and we’ve driven it twice between LA and the Bay Area. It had so much pull that we could pass small cars on I‑5 over the Transverse Ranges with a ton of cargo in the back.

Some aspects of this truck are weird—for example, it still uses a mechanical key. The hidden door handle is fun.

This is an XLT—the mid‑range trim, but basically the entry trim for consumers (you rarely see anyone pick the XL work‑truck for home use). Inside, there’s a big screen and automatic A/C. No leather seats—not even an option on this trim.

What surprised us was NVH: far better than expected, barely truck‑like. Close the door and the surroundings go quiet. We’re curious how much further it’s dialed up on the luxury trims (King Ranch and Platinum).

Power is magnificent. As noted, it has a 400‑hp V6 and about 510 lb‑ft of torque. One of our team members had a first‑gen F‑150 Raptor (with the 6.2‑liter V8 rated around 420 hp), and he says this truck feels far more powerful. The ride is smooth—especially with a load in the bed. You can still tell it’s a body‑on‑frame vehicle, but it already feels more comfortable than many SUVs. Now we’re curious how the new Expedition and Navigator ride.

We only had it for about 20 hours, and we were sad to hand it back. We almost went for a minivan, since we weren’t sure we could fit all the boxes in the bed, but now we can say we don’t regret it at all.

Any downside? Like everything else, it’s gotten more expensive. The new F‑150 starts at $38,810, and an XLT with the 3.5‑liter engine runs at least $50,000—more than the fully loaded Raptor our teammate bought in 2011. Today’s Raptor starts around $80,000, and the V8 version (supercharged though) pushes past $110,000.

Is that the cost of “Made in America”? We don’t know. There’s been significant inflation over the last 15 years. But if you use China as a comparison, Chinese cars are much fancier—and cheaper—than 15 years ago. The current administration has also raised tariffs on imported cars so the domestic industry can survive.

But one thing’s for sure: Americans know how to build good trucks—and, so far, they’re doing it better than anyone else.